Introduction

Cambodia historically has had a troubled past, particularly for its youth. Generations of Cambodians are affected by the prevalence of drugs, crime and a history of bloodshed dating back to the Khmer Rouge incidents of the late 60s and 70s (Chandler, 2001). While the world has moved towards a more globalized intercultural society, it is difficult for youth to find education and skills that will prepare them for the fast-paced interconnectedness around them. Small organizations within Cambodia continue to strive for a better understanding of intercultural ideals by incorporating simple ideas such as agricultural farming as a start to building towards a more sustainable future. As a nascent NGO, Living Water Farm (LWF) has had to deal with numerous constraints of working in the cultural context of Cambodia. Chief among them have been engaging as a Christian organization in a skeptical and majority Buddhist context, incorporating relevant programs for youth who are increasingly interested in working in urban settings, and poor agricultural productivity which has caused farmers to lose faith in agriculture as a viable livelihood option.

Vatanak Vong, Program Director of LWF, has expressed interest in engaging Cambodian youth by providing support around their personal and professional development, role in their community, and improving youth’s overall interest in farming as a viable livelihood option. With the growing hope to continue to support Cambodian youth, LWF is working to better understand and support the dreams of youth while also deepening their understanding of the importance of agriculture in Cambodia. With this in mind, we conducted a review of the relevant literature to deepen our understanding of (1) the constraints in engaging youth in community development in Cambodia; (2) operating as a Christian organization in a skeptical and majority Buddhist society. Based on this research, we have developed a possible guiding framework for Living Water Farm as it seeks to engage Cambodian youth for their self-development as a faith-based agricultural organization.

Background/Literature review

A). Youth Development and Community Involvement

In Cambodian society, young people often negotiate between hopes of a better life offered by peace, economic growth and relative political stability, and daily experiences of myriad problems including poverty, violence, political suppression and health risks (Peou, 2015). Researchers have found the importance of engaging youth in community, especially for promoting education and sustainability with rural youth in Southeast Asia (Gallagher et al., 2000; Apinundecha et al., 2007). Community and youth development are closely related because both hinge on the basic health of the functions of family and are long-term strategies for reducing youth and community problems (Sanoff, 2000). LWF focuses much of its education around agriculture with opportunities to learn English education as well. As Vatanak has explained, LWF is also focused on addressing these social and economic issues through agricultural education, as well as keeping youth engaged in their own community other than leaving for the cities. Research finds that youth are more likely to stay embedded in their communities when strong community partnerships among NGOs, local authorities, and youth’s family members are present (Khin, 2017). Research in rural Cambodia indicates that poverty and the pressure to migrate for work are a significant barrier to educational attainment, despite the perceived benefits of education by youth and encouragement by families (Tost, 2019). Youth within Cambodia often look at the future as open and accessible or closed and predetermined. The pressure to migrate is something that Vatanak has seen frequently in his urban area. Through the study, results indicate that the NGO programs were viewed more positively than the government school (Tost, 2019). This meant that youth found that they were able to get an education that they enjoyed through a dedicated NGO. Students also reported getting significantly more benefit from the NGO school than from the government school. With this research in mind, LWF can use a community participatory approach to engage youth by providing education in agriculture that they can bring back to their rural communities.

With the pressure to migrate, Vatanak has described witnessing much of the stresses within the youth in Cambodia. The rates of posttraumatic stress symptoms among Cambodian youth are high, Cambodian children face long standing sociopolitical, intergenerational, and cultural factors that compound the impact of other trauma (Figge 2020). LWF works to serve as an outlet for these stresses that the youth carry in addition to providing them with opportunities through their organization. As LWF provides an outlet for these young people, it is important to recognize the trauma in which a student may have experienced. To ignore these problems as possible sequelae of trauma may be to ignore the problems most worrisome and prevalent to this population (Figge 2020).

In addition, gender often plays an important role in engaging rural youth in the community (Ferris et al., 2013). An important aspect for LWF to consider when thinking about engaging youth might be to look at how gender norms and expectations play into the trend of rural flight. In a study conducted by Bylander (2015), it is evident that young Cambodian men and women are trying to cultivate a space for themselves in a changing society. But they are motivated by different factors that inform whether or not they stay in local contexts or migrate to cities or abroad. Bylander finds that young men face extreme social pressures to migrate and experience negative social judgments if they seek to stay put and work in rural areas. Young women, on the other hand, face much less pressure to migrate and are perceived to have meaningful alternative livelihoods and places in the village context. As LWF seeks to convince youth that farming is a viable and respectable livelihood option, it may need to pay particular attention to the social constraints placed on young men who face serious societal pressure to leave the rural communities.

With the LWF’s work in showing the importance and impact of agriculture education to Cambodian youth, there is a possibility that there can be a shift in the societal expectations placed on youth. Youths are more likely to stay embedded in their communities when strong community partnerships among NGOs, local authorities, and youth’s family members are present Khin (2017). For LWF, as Khin’s work (2017) seems to suggest, the promotion of better social cohesion among all relevant entities engaged in community development around LWF might go a long way in encouraging youth to stay embedded in their communities. Connecting with other Cambodian NGOs engaging youth in development to share lessons learned and best practices may be a helpful tactic. Additionally, Khin’s research has demonstrated the need for NGOs promoting youth community development work to be fully aware of the community’s perceptions and fears of youth engagement and adapt to these perceptions.

B). Operating as a faith – based organization in Cambodia

In addition, gender often plays an important role in engaging rural youth in the community (Ferris et al., 2013). An important aspect for LWF to consider when thinking about engaging youth might be to look at how gender norms and expectations play into the trend of rural flight. In a study conducted by Bylander (2015), it is evident that young Cambodian men and women are trying to cultivate a space for themselves in a changing society. But they are motivated by different factors that inform whether or not they stay in local contexts or migrate to cities or abroad. Bylander finds that young men face extreme social pressures to migrate and experience negative social judgments if they seek to stay put and work in rural areas. Young women, on the other hand, face much less pressure to migrate and are perceived to have meaningful alternative livelihoods and places in the village context. As LWF seeks to convince youth that farming is a viable and respectable livelihood option, it may need to pay particular attention to the social constraints placed on young men who face serious societal pressure to leave the rural communities.

With the LWF’s work in showing the importance and impact of agriculture education to Cambodian youth, there is a possibility that there can be a shift in the societal expectations placed on youth. Youths are more likely to stay embedded in their communities when strong community partnerships among NGOs, local authorities, and youth’s family members are present Khin (2017). For LWF, as Khin’s work (2017) seems to suggest, the promotion of better social cohesion among all relevant entities engaged in community development around LWF might go a long way in encouraging youth to stay embedded in their communities. Connecting with other Cambodian NGOs engaging youth in development to share lessons learned and best practices may be a helpful tactic. Additionally, Khin’s research has demonstrated the need for NGOs promoting youth community development work to be fully aware of the community’s perceptions and fears of youth engagement and adapt to these perceptions.

C). Engaging Cambodian Youth in Agricultural Projects

Combatting increased globalization and poor agricultural productivity, NGOs and government entities around the globe are struggling to mobilize youth to stay engaged in the agricultural sector. Despite these efforts, there is a tremendous lack of decent employment opportunities along the agricultural value chain in rural areas. This is particularly true in the case of Cambodia (Düerkop et al. 2010). Given the lack of opportunity, it is understandable that Cambodian youth seek employment in other sectors. In a cross-regional study conducted on youth in India, Philippines, Mexico, Morocco, Mali and Nigeria, most young men and women reported career aspirations in formal blue collar and white-collar sectors (Elias et al., 2018). This is consistent with the trends observed by Living Water Farm in Cambodia. In Cambodia, it has been observed that there are extreme societal pressures on youth to migrate and leave rural areas to pursue higher paying jobs in urban centers or abroad (Bylander, 2015). Cambodian youth, particularly young men, who do not find blue collar work beyond rural areas are stigmatized and may be judged poorly by their communities and Cambodian society as a whole.

There is also a complex gender lens that further complicates the notion of engaging youth in agricultural work. According to a report published by the Parliamentary Institute of Cambodia, agriculture is the primary source of employment for both Cambodian men and women, but gender norms and expectations play a critical role in this sector (Leapheng, 2018). While young men face extreme societal pressure to leave the poverty associated with smallholder agricultural work, young women face much less pressure to migrate away from rural areas. In fact, young women are perceived to have many meaningful livelihood options in the rural context (Bylander, 2015). In the same cross-regional study referenced earlier, it was noted that across the cultural contexts of Latin America, Africa, and Asia, there tend to be restrictions on what women in agricultural work do (Elias et al. 2018). For example, men tend to be responsible for tiling the land and preparing the soil while women may be responsible for planting. In addition to these gender roles, female youth in Cambodia often have the dual burden of assisting their parents in the household and in family work more than their male siblings. Young Cambodian women also have less access to land ownership than men (Düerkop et al. 2010). Given that agricultural activities are often gendered and that these gender roles often complement the completion of agricultural tasks, the loss of young male Cambodian youth in rural agricultural work could severely disrupt the productivity of the smallholder sector.

This is particularly worrisome given that the success of the agriculture sector and increased productivity/financial viability is one of the primary motivators for youth to enter into the sector. The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) published a study on methods to prepare and motivate youth for active engagement in the Agriculture sector. One of the crucial aspects they identify for successfully engaging Cambodian youth in the agriculture sector is the need to demonstrate a competitive level of income (Düerkop et al. 2010). Therefore, it will be increasingly important to consider the potential effects of an increasingly female-driven workforce on perceived agricultural productivity and financial viability of smallholder farms. The ways in which gender norms and expectations shape the agriculture sector further complicates the notion of engaging Cambodian youth in agriculture. For Living Water Farm, it will be important to adopt methods that are equitable, sustainable, and agriculturally and financially productive.

The resources that were presented in this review were used to show the benefits and challenges that can be incorporated into Living Water Farm’s organization. The three aforementioned areas are categorized to support Living Water Farm’s mission: Youth Development & Community Involvement, operating as a Faith Based Organizations within Cambodia, and Engaging Youth in Agricultural Projects. The variety of the literature reviewed provided deeper understanding around the influences and constraints in engaging youth in community development in Cambodia and operating as a Christian organization in a skeptical and majority Buddhist society. By no means is this team experts in the field within the constraints that LWF faces, however, we have identified these resources that reference many of the challenges listed by Vatanak. We further detail these reviews in connection to the challenges of LWF. These resources are meant to serve as a way to promote the work at LWF in which Vatanak and his team can further decide which of these resources are of benefit to them.

Methodology

We were first introduced to Vatanak and the Living Water Farm via email introduction. We quickly aimed to find a mutual meeting time that worked both for the US team and Vatanak who is 12 hours ahead in Phnom Penh. The objective of our first meeting was to spend some time getting to know each other, our backgrounds, degrees and interests, etc. We also shared our experiences traveling and working in different cultural settings. Unfortunately, only one team member had visited Cambodia before and was relatively familiar with some of the cultural aspects of the country. This meeting also served as a way to learn more about Living Water Farm (i.e., how it was created, where the idea came from, its goals and objectives for the future). Vatanak’s familiarity with American cultural norms and identities helped in facilitate this discussion. As a team, this first meeting was an important aspect of the “welcoming stage” (Zander et al. 2013) that is necessary for collaboration of a new multicultural (and virtual). This stage was essential for relationship building and we found it a worth endeavor before jumping into the more goal-oriented discussion of deliverables which became the focus of future meetings.

Internally, we formulated a team agreement reflecting a lot of the points discussed in our initial meeting. In this, we detailed responsibilities, goals and objectives, and strengths of each team member. The team agreement helped us to stay on track for the remaining aspects of the project. A week later after the Team agreement was formed, we prepared for a more targeted second meeting with Living Water Farm that focused on how we could best serve the organization in creating a framework to help achieve their goals. For the second meeting, our team worked to create a needs assessment to better understand LWF’s constraints as an organization, its targets, goals and intended outcomes for 2021. The needs assessment allowed the team to identify possible entry points that informed the direction of a framework. Through our conversations, it became evident that LWF faces some unique leadership challenges working as a Christian-based organization in a majority Buddhist country. In addition to this, the organization spoke to the issue of engaging youth in the agriculture sector and expressed interest in working with youth to be ready for their next steps in education and later careers. The organization also identified the issue of having limited English proficiency among LWF staff and limited access to academic research to aid in the development of relevant, creative, and evidence-based approaches to these constraints. Based on these findings, we have developed easy-to-use guidance, informed by the relevant literature, to address LWF’s concerns in the areas of (1) youth development and community involvement, (2) operating as a faith-based organization in Cambodia, and (3) engaging Cambodian youth in agriculture. The framework presented in the section below is a result of our coursework, research, and in-depth conversations with the Program Director of Living Water Farm.

A framework for Living Water Farm

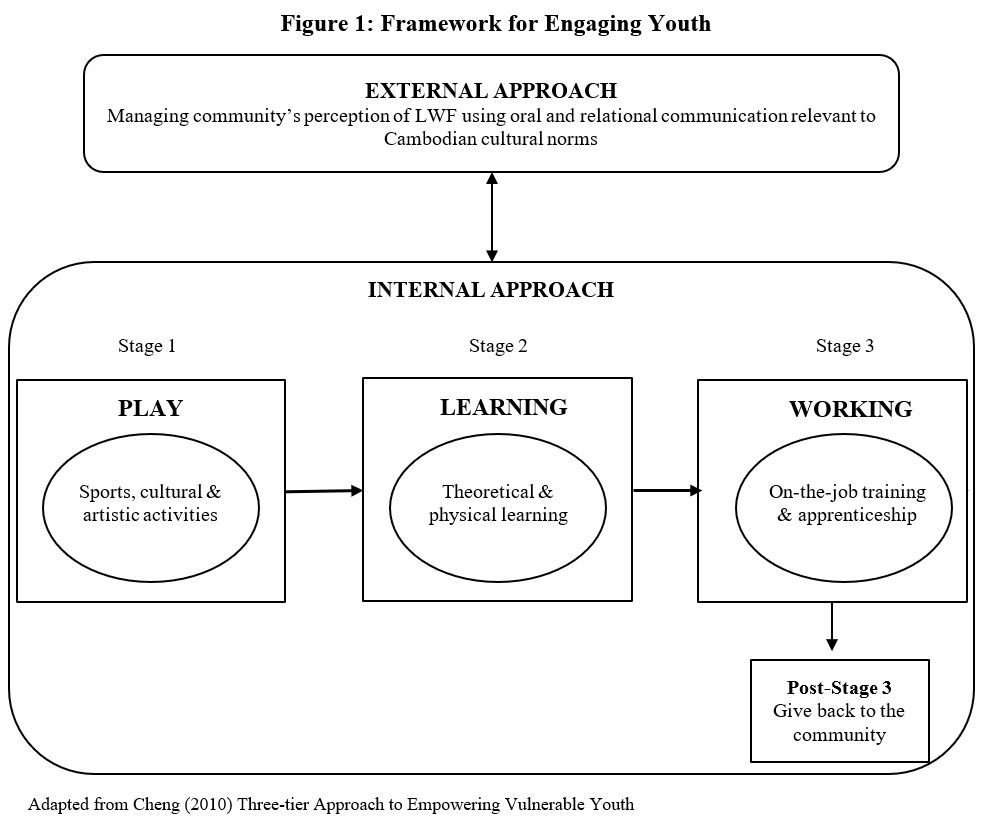

We have adapted the 3-tier model for youth development and empowerment presented by Cheng (2010) to address some of Living Water Farm’s constraints as a faith-based agricultural organization in order to provide some practical recommendations and possible guidance on how best to engage Cambodian youth in this context. We have organized this framework into two overarching categories: external and internal approaches. As a Christian organization, LWF is uniquely aware of how it is perceived by the majority Buddhist community. In order to effectively engage youth, LWF needs to manage these external perceptions to encourage and facilitate youth involvement. This makes up the organization’s external approach. The organization’s internal approach, here, specifically references how it can engage with Cambodian youth in particular. These approaches and stages are detailed below and depicted in Figure 1 below.

a. External Approach

As a faith-based organization, Living Water Farm is very aware of how it is perceived by the surrounding Buddhist majority community. Much of the guidance we have identified in the literature to navigate this complex situation are tactics that Living Water Farm successfully uses already. Nevertheless, it is important for LWF to consistently manage these external perceptions in order to effectively encourage youth engagement. Suh (2017) notes that Cambodian culture relies largely on oral and relational communication; this is how relationships of trust and mutual understanding are created. With this in mind, Living Water Farm should continue to mitigate any negative perceptions it may have by building these bridges to the surrounding community, local stakeholders, and local government entities. This means that the best way for Living Water Farm to promote the work in agriculture and youth development, is by speaking to and developing relationships with more of the Cambodian population. Whether they are Christian, Buddhist or of other faiths, the common culture for communication between Cambodian is by word of mouth. The warmth displayed when visiting someone in their village or in their home speaks to the closeness exhibited in highlighting what both have in common: both are Cambodian. While other organizations elsewhere may promote events and work by using flyers, posters and online advertisements, what will help Living Water Farm is continued awareness of the work they do through word of mouth. We label this the external approach, which will help Living Water Farm keep a positive reputation in the community by using oral and relational communication, an important aspect to Cambodian culture.

b. Internal Approach

By organizing events that revolve around community culture and organizing activities that are non-religious in nature, LWF will attract more of the Cambodian population. Suh’s work suggests that given the circumstances, these faith-based organizations have a unique opportunity to showcase the good-natured work they are trying to do for all Cambodian people. Living Water Farm already does this but must make this one of the main objectives for their activities to appeal to others and gain trust amongst the community.

Play is a natural component of a child’s development that allows them to interact and problem solve within different social settings. Play also serves the important purpose of providing a safe space for children to develop and grow. Within Cambodia, there are many stressors placed on youth that vary from societal pressures, migration pressures, and cultural impacts that can bruise the development within a child. Play will lead to increased levels of self-esteem and confidence for youth to develop guidance for the direction of their own lives (Cheng, 2010). By engaging with Cambodian youth of different religious backgrounds, this will lead to more youth moving from ethnocentric mindsets to ethnorelative beliefs such as acceptance of difference (Bennett, 1993). Therefore, relationship-building and trust are key components that can be integrated through stage 1 of the framework. Living Water Farm aims to serve its youth by providing them opportunities within their organization that they can carry with them. However, by entering numerous communities and having youth join them from various parts of Cambodia, stage one serves as a crucial piece to providing a safe environment for youth within the Living Water Farm walls. NGO facilitators can engage youth in a space that they feel safe, while allowing children to open up about their interests in further learning and future career work. By putting time and effort into understanding the youth, there is respect for their stories and the places that got them to where they are today. In order to build relationships and build that trust, it is crucial to organize activities in a culturally relevant way (Suh, 2017). Creating outlets for the youth such as sports, and cultural and artistic activities that allow them to have a safe space to meet their social emotional needs. Cheng outlines that most NGOs in his 2010 study were able to provide a space for children to play and indulge in cultural activities such as drama, dance and singing (Cheng, 2010). It is in this space that youth can be engaged in their interests in learning and possibly working (Cheng, 2010). By providing these activities, Learning Water Farm will not only build the knowledge in agriculture education but also provide youth the opportunity for personal growth.

LWF already has a space for learning and practical skills training. By continuing work in computer skills in the classroom, and farming skills outdoors, LWF only requires a space for the informal setting, the playground. Before engaging youth with educational and practical tools that will allow them to excel, LWF must engage them at their own level: in the playground. This will lead to relationship building between youth and LWF staff that will create trust in pursuing further skills in education and farming. The youth need to have a desire to be there, instead of being there solely for the necessity of future employment prospects. The youth will learn what they want to do, as they are exposed to various vocational education tools. From this, they will develop a personality for what their future will look like, leading to more concentrated vocational skills that they may learn with LWF.

Students learning computer skills

Kids practicing building hydro-system

Students registering

c. Internal Approach : Stage 2

Stage 2 of our framework seeks to specifically address the “Learning” stage of youth engagement. This stage seeks to provide LWF with guidance on how best to teach agriculture to Cambodian youth who are motivated by a need for improved incomes and face societal pressures to leave rural areas. One of the key challenges in engaging youth in agriculture for LWF is that there is very little motivation to stay in rural areas and societal pressures to migrate to find better opportunities elsewhere. Living Water Farm acknowledges the need to promote agriculture as a financially viable option for Cambodian youth. Düerkop et al. (2010) agree that in order to correctly motivate youth in the agriculture sector, organizations and leaders need to demonstrate the saliency of agriculture-based income. During LWF’s agricultural training, one focus might be on agricultural business development skills. Youth agricultural training programs should include planning and running agricultural micro-enterprises as a business and would be complimented by coaching and mentorship of people with agricultural business experience. The programs should also provide life skills focusing on self-empowerment, problem-solving, decision-making, and building a business-based mentality for youth in farming. Agricultural business training at Living Water Farm could be modeled on the Young Agri-Entrepreneurs (YAE) one-year training program providing rural youth with agricultural-business skills (Düerkop et al. 2010). Promoting agricultural entrepreneurship, as opposed to traditional rural farming, is one possible way that Living Water Farm can change youths’ and adults’ perceptions of agricultural work from being antiquated and financially unrealistic to respectable and high-income generating. In order for this model to work, authors have emphasized the importance of promoting continued education for both young men and women considering the agricultural sector. The cognitive development and skills from staying in school until they receive diplomas will enable them to further develop cognitive skills that will assist them in becoming productive agricultural entrepreneurs (Düerkop et al., 2010).

d. Internal Approach : Stage 3

Stage 3 of this framework includes the working portion of their farming project. After speaking with Vatanak and hearing of the unique challenges Living Water Farm faces, this stage of our framework includes specific keys to success. The three objectives, adapted from Frame (2017)’s study to meet the context of LWF’s needs, are listed below:

1. Demonstrating great passion, motivation and dedication in your work

2. Coaching and Mentorship

3. Continue to advocate and emphasize the importance of agricultural need

Frame’s (2017) study mentions that the passion, motivation and dedication exhibited by faith-based organizations in Cambodia to help those less fortunate than them has proven their good nature. This practice of working towards helping the goals of others has proven to develop relationships of trust, understanding and mutual respect. If Living Water Farm aims to help at-risk youth, younger generations and those exploited by lives of drugs and crime, their dedication and passion for doing the right thing will speak more to growing their organization’s mission and vision further across Cambodia.

The second key to Stage 3 is coaching and mentorship. The success of job training is highly depended upon mentorship by others who are experts in their fields. Those trained to work with youth to develop their skills will need to continuously strive to teach and refine youth’s skills along the way. As discussed in Stage 2, the risks associated with agricultural entrepreneurship is particularly challenging for rural youth, so it is crucial to establish post-training support, such as mentoring to minimize the risk. By building on stage 2, Stage 3 allows youth to apply what they have learned under the supervision of those who have mastered it.

Finally, LWF must continue to advocate for agricultural development. This is the most important objective of stage 3. Without the constant reminder that one of the keys to sustainability is providing for oneself, the importance of agriculture will be forgotten by the youth. Vatanak and the rest of Living Water Farm must be able to highlight success and look to use young leaders in their program as leaders in their community, and to give back to future youth in informing them about the importance of agricultural needs. Youth will constantly be looking towards other trades in an ever-increasing globalization and tech-connected world but with role models that have “graduated” from the program and invested in their own local community, youth will see that there is success to be had in farming God’s way.

These 3 objectives listed above are not new concepts for Living Water Farm. Living Water Farm has been working towards these goals and demonstrated it by proving their dedication to their work, serving as role models and speaking to the community about the importance of sustainable agriculture. These 3 objectives must be continually applied in the work Living Water Farm does to further promote knowledge of the faith-based organization that looks to expand for 2021.

e. Internal Approach : Stage 3

The empowerment of youth and the community will not stop after the youth complete stage 3. The post-Stage 3 objective is to have youth giving back to the community and make the programs more sustainable. LWF can build a long-term relationship with youth from the programs. It would not be practical to predict that all youth participants will engage in farming or choose to stay in the community after finishing the program with LWF, but those who do should be encouraged to serve as role models. Based on Cambodian’s current economic and internal migration situation (Diepart & Ngin, 2020), some youth will still migrate to work in the cities after the LWF program, while the rest might start their farming career with an entrepreneurial mindset.

For those who stayed in the community to farm, LWF can work closely with them. LWF can invite them back to the program to work as volunteers and career coaches. Compared to coaches unfamiliar with the program, they are more familiar with the community and share a stronger bond with the participants. They can teach the participants farming and business skills, especially how to run their farm like a business in their community using the local resources and networks.

For those who migrate to cities, LWF can also work with them to help them give back to their communities. On the one hand, they can work as program volunteers when they return to the community. On the other hand, they can play the liaison role between the rural farming entrepreneurs and the city farm product businesses. They can use their knowledge and working experience in the cities to help the rural farmer build their farming outcome as a relevantly high value-added business product other than traditionally low priced raw materials, as well as help the rural farmers find marketing channels for their products.

In short, through engaging the youth participants after they finish the program, LWF will be able to not only make the LWF programs more sustainable but also build a stronger and empowered community.

Limitation of this framework

There are a number of possible limitations to this framework. One of LWF’s biggest challenges as a Christian organization is to manage how it is perceived by the majority Buddhist Cambodian communities in which it works. We present some possible ways to mitigate negative perceptions and improve relationships with Buddhist communities. However, there may always be the innate barriers to operating as a minority faith-based organization in a skeptical majority-Buddhist and/or increasingly secular society. Despite LWF’s efforts, it may not always be able to control how it is perceived externally. While certain communities may be willing to engage with LWF, they may always encounter some individuals or communities who are not willing to see past its faith-based mission.

One other possible limitation of this framework is that it requires a lot of organizational capacity in the form of management skills and coordination between various stakeholders. It also requires a significant time investment on the part of the Program Director and other organizational staff. With the strong component of outreach, LWF can run into the barrier of not having the organizational capacity to fulfill the need of outreach to communities.

Lastly, internal aspects of this framework are specifically modeled for LWF as it engages with Cambodian youth (pre-teen to teenagers), specifically in the agriculture sector. This framework does not account for any engagement LWF might consider currently or in the future with younger Cambodian children outside of the agriculture sector. As LWF seeks to operationalize this framework, it should be mindful of the age group that is being targeted.

References

Apinundecha, C., Laohasiriwong, W., Cameron, M. P., & Lim, S. (2007). A community participation intervention to reduce HIV/AIDS stigma, Nakhon Ratchasima province, northeast Thailand. AIDS Care, 19(9), 1157–1165. https://doi-org.proxy-um.researchport.umd.edu/10.1080/09540120701335204

Bennett, Milton J. “Towards Ethnorelativism: A Developmental Model of Intercultural Sensitivity.” Education for the Intercultural Experience. Ed. R.M. Paige. 2nd edition. Yarmouth, ME: Intercultural Press, 1993. 21-71.

Bylander, M. (2015). Contested mobilities: Gendered migration pressures among Cambodian youth. Gender, Place & Culture, 22(8), 1124–1140. https://doi.org/10.1080/0966369X.2014.939154

Chandler, D. (2001). Cambodia: A historical overview. Asia Society Center for Global Education.

Cheng, Hsuan. 2010. Case studies of integrated pedagogy in vocational education: A three-tier approach to empowering vulnerable youth in urban Cambodia. International Journal of Education Development. Volume 30, Issue 4. July 2010, Pg. 438-446. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0738059310000039

Diepart, J. C., & Ngin, C. (2020). Internal Migration in Cambodia. In Internal Migration in the Countries of Asia (pp. 137-162). Springer, Cham.

Düerkop, L., Bolliger, A., & Scheeve, W. (2010). Business development and youth in rural Cambodia. Rural 21: The International Journal for Rural Development, 44(3), 22-24.

Earley, Christopher P & Mosakowski, Elaine. October 2004. Cultural Intelligence. Harvard Business Review.

Elias, M., Mudege, N., Lopez, D., Najjar, D., Kandiwa, V., Luis, J., Yila, J., Tegbaru, A., Ibrahim, G., Badstue, L., Njuguna-Mungai, E., & Bentaibi, A. (2018). Gendered aspirations and occupations among rural youth in agriculture and beyond: A cross-regional perspective. 3(1), 82–107.

Ferris, K. A., Oosterhoff, B., & Metzger, A. (2013). Organized Activity Involvement Among Rural Youth: Gender Differences in Associations Between Activity Type and Developmental Outcomes. Journal of Research in Rural Education, 28(15), 1–16.

Feldt, H. (2019). Preparing and accessing decent work amongst rural youth in Cambodia. The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nationals & Humboldt University of Berlin.

Frame, J. (2017). Exploring the approaches to care of faith-based and secular NGOs in Cambodia that serve victims of trafficking, exploitation, and those involved in sex work. International journal of sociology and social policy.

Figge, M. (2020). Key expressions of trauma-related distress in Cambodian children: A step toward culturally sensitive trauma assessment and intervention. Transcultural Psychiatry, 1363461520906008–1363461520906008. https://doi.org/10.1177/1363461520906008

Gallagher, J., Wheeler, C., McDonough, M. et al. Sustainable Environmental Education for a Sustainable Environment: Lessons from Thailand for Other Nations. Water, Air, & Soil Pollution 123, 489–503 (2000). https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1005200612849

Khin, S. A. (2017). Youth Participation in Community Development: A Case Study of Youth in Takeo Province, Cambodia[School of Geography, Environment and Earth Sciences, Victoria University of Wellington]. http://hdl.handle.net/10063/6715

Leapheng, P. (2018). The Important Role of Cambodian women in the Agriculture Sector. Parliamentary Institute of Cambodia.

Peou, C., & Zinn, J. (2015). Cambodian youth managing expectations and uncertainties of the life course – a typology of biographical management. Journal of Youth Studies, 18(6), 726–742. https://doi-org.proxygw.wrlc.org/10.1080/13676261.2014.992328

Sanoff, H. (2000). Community participation methods in design and planning. Wiley.

Suh, G. S. (2017). Exploring a Contextualized Leadership Development Model Built on Spiritual Formation for Emerging Christian Leaders in Urban Cambodia. Fuller Theological Seminary, School of Intercultural Studies, ProQuest Dissertations Publishing.

Tost, J., Spires, B., & Sokleng In. (2019). Cambodian youth perspectives on social and educational barriers: An exploratory case study in a rural border region. Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies in Education, 8(2), 130–146. https://doi-org.proxygw.wrlc.org/10.32674/jise.vi0.1227

Zander, L., Zettinig, P., & Mäkelä, K. (2013). Leading global virtual teams to success. Organizational Dynamics, 42(3), 228–237. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.orgdyn.2013.06.008